Thought Leadership

Knowledge is meant to be shared. Although the proprietary nature of some of our engagements limits distribution, we are committed to offering valuable insights and expert views on selected topics to the public whenever possible. Click the hyperlinked images below to read more:

“The hidden story of nonprofit mortality”

Published by Innovators Magazine, January 21, 2026

“When technology shouldn’t replace humans”

Published by Innovators Magazine, November 11, 2025

“Lessons from apocalyptic thinking”

Published by Innovators Magazine, August 12, 2025

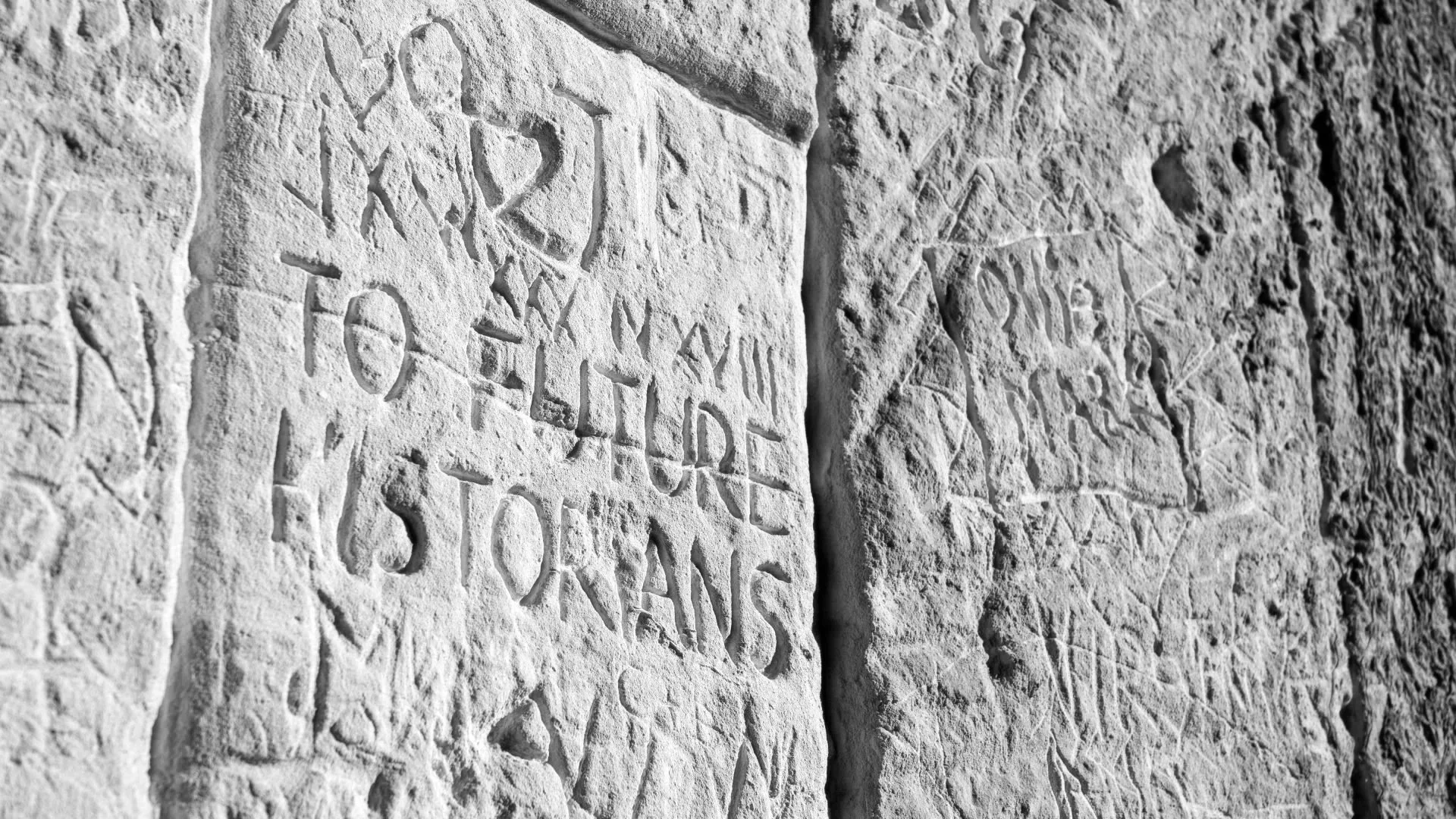

“AI unlocks new golden age of the consulting historian”

Published by Innovators Magazine, May 8, 2025

“It’s time we ditch our obsession with numbers”

Published by Fast Company, April 8, 2025

“How constraints can make you more creative”

Published by Innovators Magazine, January 8, 2025

“How to be a better interviewer and conversationalist”

Published by Fast Company, January 6, 2025

“From conservation to climate”

Published by Alliance Magazine, October 28, 2024

“Ageism is bad for business”

Published by Fast Company, October 11, 2024

“How to generate new ideas”

Published by Innovators Magazine, September 4, 2024

“Businesses have the memory to be more innovative”

Published by Innovators Magazine, August 13, 2024

“The origins of West Coast philanthropy”

Published by Alliance Magazine, July 4, 2024

“Creativity: the leadership skill we all need”

Published by Innovators Magazine, July 26, 2024

“Why History is Important to the Future of Feminism”

Published by Canadian Women’s Foundation, June 4, 2019

“Review of Roche, The Third Reich’s Elite Schools”

Published by H-German, September 7, 2022